Guest post from our Week 4 Friend of the Week, Stephen Angell. The weekly theme was “The Future of History.” Below, Steve describes some of the talks he attended, and offers a Quaker response. In addition to being our Friend of the Week, Stephen W. Angell also serves as Leatherock Professor of Quaker Studies at Earlham School of Religion.

The Future of History

The theme of Chautauqua Institution this week was the “future of history.” So, what do Quakers have to say about the future of history? It was my task this week to help our f/Friends figure that out. (Let me just give a shout out to Gary and Kriss Miller, our absolutely wonderful hosts at Quaker House, without whom much or all of this would have been impossible. Thanks, Friends!) Back to the theme: It’s a marvelously mystical yet practical topic, and everybody has a different approach to it.

I’ll start with what others had to say about the theme. The historian Jon Meacham concentrated on the challenges of the current American political system, where the right is currently pursuing different goals than the center and the left. To the extent that the right is contemplating and actively pursuing obstructing the peaceful transfer of power, Meacham observed that much pressure lies on the center and left to work with renewed vigor to preserve the American constitutional system. If all sides in the political spectrum give in and place such constitutional bedrock principles as the peaceful transfer of power as a secondary goal at best, then the American constitutional system that has endured for more than two centuries is in even greater danger than it is now. Meacham spiced up his presentation with conversations with various famous and ordinary people, especially one of his biographical subjects, George H. W. Bush.

Diplomat and college administrator Eliot Cohen explored the current controversy over preservation of statues. Cohen is all for taking down statues of Confederate icons such as Robert E. Lee, relegating such statuary to cemeteries, museums, and battlefields. But he argued for preserving statues of flawed heroes such as Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and argued that Benedict Arnold deserves a better reputation than he currently has, because at the Battle of Saratoga he saved the cause of American independence, something of more significance than his later attempts to betray the new nation and to undermine its independence.

Historian Barbara Savage, whose presentation was sponsored by the African American Heritage House, talked extensively about the fascinating subject of her forthcoming biography, Merze Tate, a long time, well traveled, well published, brilliant, and all-but-forgotten African-American diplomatic historian who taught at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Author and director Bill Barclay and a brilliant ensemble of actors and musicians presented a most educational musical about Joseph Bologne Chevalier de Saint Georges, the “Black Mozart” whose music was all-but-forgotten until very recently. Rediscoveries like these are important! For history to have a rich future, as we all hope that it does, it is of great importance to delve more fully into the riches of the past in order to inform our outlook on the future.

Well, what do Quakers have to say about all this?

I come to that subject having authored or co-authored ten books on Quaker and other histories: The Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies (Oxford University Press, 2013); Black Fire: African American Quakers on Spirituality and Human Rights (Quaker Press of FGC, 2011); The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism (Cambridge University Press, 2018); Indiana Trainwreck: Divisions in Indiana Quaker Communities over Inclusion of Homosexuals, Church Authority, Christ, and the Bible (Quaker Theology Press, 2019), among others.

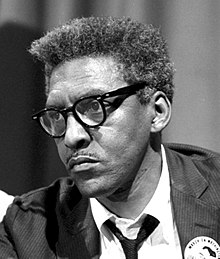

In Black Fire, my co-authors, Hal Weaver and Paul Kriese, and I attempted to bring to life some Black Quakers who had been all-but-forgotten or who have not received the attention they deserve, such as Bayard Rustin, Sarah Mapps Douglass, Barrington Dunbar, Mahalah Ashley Dickerson, Jean Toomer, Helen Morgan Books, and many more. Recovery of vital parts of our past is important for Quakers, too.

The number of Quakers in their ancestral homelands of Britain and North America have been declining in recent decades, while the number of Quakers in the global South have been growing. We need to hear more of the stories of Quakers in the global South. The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism gives a good overview of these phenomena. But we also need to hear more Quaker voices from the global South. One work that makes a modest start in this direction is the history of some of the Quakers in Bolivia recently assembled by a bi-national team: See Nancy J. Thomas, A Long Walk, a Gradual Ascent: The Story of the Bolivian Friends Church in its Context of Conflict (Wipf and Stock, 2019).

Much of Quakerism today is characterized by theological diversity. How to cope with that diversity, and the conflict that often results from it, is explored in Indiana Trainwreck: Divisions in Indiana Quaker Communities over Inclusion of Homosexuals, Church Authority, Christ, and the Bible. This explores one of several divisions that have occurred among primarily pastoral Quakers in the 2010s. Chuck Fager, Jade Souza and I have brought out a series of three books on what we call “The Separation Generation,” of which Indiana Trainwreck was the first. My own view: separation is the middle option. If Friends of varying theological persuasions can find a way to really listen to one another and to continue to work together fruitfully, that is the best. Outright fighting and name-calling is the worst. Separation is preferable to that.

Like many of the speakers this week, I emphasized going back to the well of history, and continuing to explore the vision and insight of Quakers in the past, especially the first generation of Friends. Like many others, I have toured the 1652 country in the North of England where Quakers first became a vital movement. With Ben Dandelion, I have climbed Pendle Hill, as Quaker founder George Fox and his traveling companion Richard Farnworth did in 1652. From the chilly summit of Pendle Hill, one can see quite far. In 1652, from those heights, in the midst of many convincements of people becoming Friends, Fox saw “a great people to be gathered.” Might we be able to see the same? My bet is that we can, and we will.

Books mentioned in this blogpost:

A Long Walk, A Gradual Ascent: https://www.amazon.com/Gradual-Ascent-American-Society-Missiology/dp/1532679769

The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism: https://www.amazon.com/Cambridge-Companion-Quakerism-Companions-Religion/dp/1316501949

Black Fire: https://quakerbooks.org/products/black-fire-2251

Indiana Trainwreck: https://afriendlyletter.com/indiana-trainwreck-trauma-in-midwestern-quakerdom/

Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies: https://www.amazon.com/Oxford-Handbook-Quaker-Studies-Handbooks/dp/0198744986