from Emily Provance, Friend in Residence

Space architecture. Science Fiction. Digital religion. Genetic engineering. Every speaker we heard this week agreed on one thing about the future: whatever it’ll be, we’re all in it together, and that is not necessarily a good thing.

The week’s theme was set up surprisingly well by Ted Chiang, who spent nearly an hour defining the differences between science fiction and fantasy, when most of us listening couldn’t figure out why. We couldn’t have known that the distinction between science and magic, between egalitarian and individualistic, between an impersonal universe and a personal universe, would be so extraordinarily relevant to the rest of the week.

Science fiction, he said, studies what happens when a new technology becomes ubiquitous: what effect does this have on the whole of society? Science fiction leaves humanity in a different place from where it started. It does not follow the hero’s journey, because the story is not about a hero, it’s about an impersonal universe that is not conscious and values nothing. It reminds us that we are not special.

But fantasy, he said in contrast, spins a tale of an individual or set of individuals with powers. These few are, for some reason, special; they are chosen by a personal universe that has some consciousness and respects individuality. Fantasy often follows the hero’s journey because it is about a hero. It reminds us that we are special.

So continued the entire arc of this week, with persistent reminders that we matter quite a lot and, at the same time, we matter not at all. The future will unfold as the cumulative result of countless individual decisions, so many that it will be impossible for any one person to alter the momentum–and yet, this wave of time we’re riding is guided by the actions we all take. We’re in this together, like it or not.

When we look at climate change or Christian nationalism or racism, this word “community,” which Friends call a testimony, becomes bigger, because now we’re talking about the future of all we’ve known, and how the story ends will depend upon the whole of humanity. Another speaker on Monday, Katharine Rhodes Henderson, admonished us to hold each other tight. That, she said, was the only way we had a hope of getting through this. But what does it mean to hold each other tight? Hold who tight? How, exactly?

Gretchen Castle, who served as our brown bag speaker on Wednesday at Quaker House, talked about the globalization of religion, particularly in the Covid era, when suddenly it became nearly as easy to worship with someone many countries away as it was to worship with one’s own local community. In some ways, this is a glorious thing. We can cross many boundaries we couldn’t before: national boundaries, language boundaries, theological boundaries, cultural boundaries. We can hold each other tight from quite far away. But resonant from that conversation, too, was something that a participant said: it’s a little too easy, with the whole world to choose from, to find someone who doesn’t bother me, someone with whom I already agree. But is that the same as loving my neighbor? If I am not longer obliged to form relationships with my immediate local community, am I finding ways to skip over the tough questions? Am I forming a safe bubble while claiming to reach across boundaries? Which are the boundaries that really matter? What does it mean to hold each other tight?

On Thursday, we heard from Ariel Ekblaw, who leads a lab at MIT with the mission of building the space technologies of the future. She and her colleagues are actively creating and testing prototypes for self-assembling space pods, musical instruments that play only in weightlessness, holodecks, radiation filters, and more. What I loved most about her presentation was the way in which she talked about assembling her team. “No one wants to live in a place designed only by engineers. So we work with artists, musicians, ethicists, communications experts…we want to inspire people by telling stories of the future extremely well.” In other words, they are building a community, a real one, where each person uses their own gifts for a united purpose.

Someone asked the obvious question: why spend money on space travel when people are starving? But of course, there was an answer to that too. “It’s not an either/or, it’s a both/and. Not to mention the ways in which our science will contribute, must contribute, to a better life on Earth. As we design radiation filters and biodomes and more efficient carbon dioxide processors, we are well aware that the work we do many eventually mitigate the effects of climate change on this planet.” This felt to me like a group of people conscious of their role in a global community

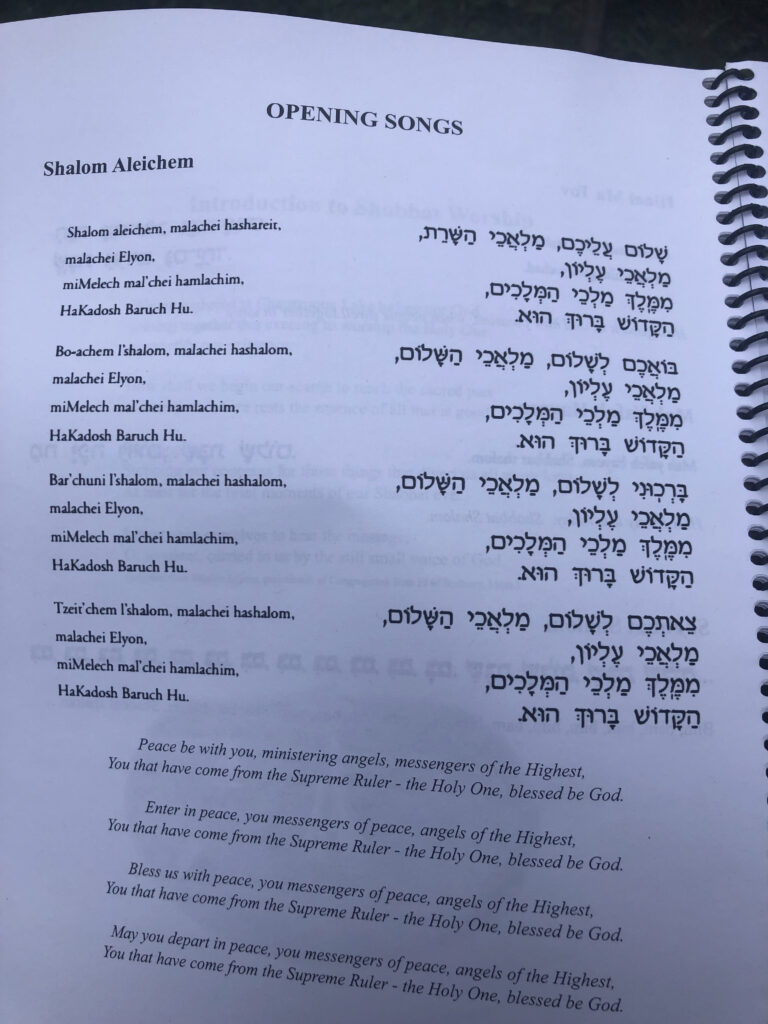

I worshiped Friday evening with the Chautauqua Hebrew Congregation. Again, I found myself witnessing a people, in this case a people who have known themselves as a people for many thousands of years. On one level, I didn’t understand the Hebrew prayers. On another level, I understood them viscerally, as a ritual that connects this people across all time, many centuries into the past and more centuries into the future. At the beginning of the service, the rabbi said, “You will notice security parked in the parking lot. This is not because there is a particular problem…it is just what most of us do now, to make sure there will not be a problem.”

What does it mean to hold each other tight?

On Thursday in morning worship, Zina Jacque told us the story of Tamar, who (righteously, in the context of the story) tricked Jacob into impregnating her and, by doing so, became a part of the lineage of Jesus. Jacque said, “All Tamar wanted was a son, and she birthed an entire religion.” This scared me. To think that one act, and a precarious one at that, could mean the existence, or not, of all Christianity. What implications does that have for my life?

But on Friday, Jacque told us of Esther, who saved the Jews from the wicked Haman. Her uncle Mordecai said to her, “If you keep silent in such a time of this, the Jews will still be saved, but you…will be destroyed.” In other words, God could find another way—but even so, intervening was Esther’s responsibility. She could have said no, but she became her fullest self by saying yes to God’s call.

Call to what? To step into her place in her community. Hold each other tight. Whatever the future will be, it will be the future of the whole global community.