Week Three: Trust

from Emily Provance, Friend in Residence

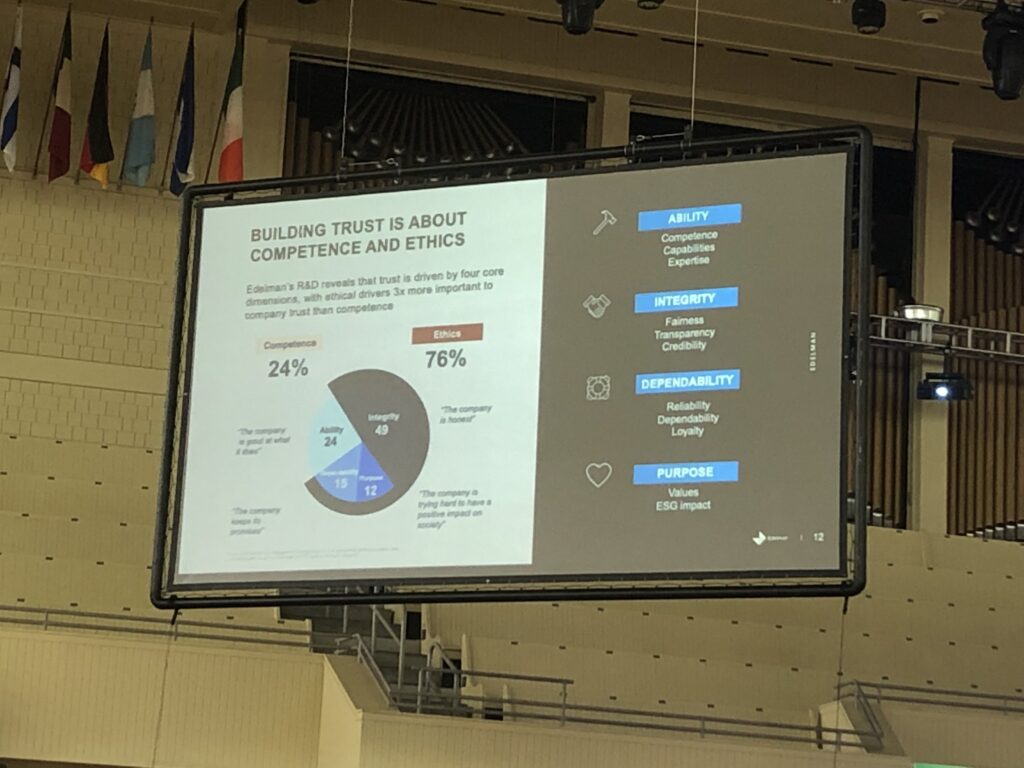

The official theme of the week was “Trust, Society, and Democracy.” I heard a lot about society and a lot about democracy but very, very little about trust. The only explicit addressing of this topic was the week’s first speaker, Richard Edelman. He established the Edelman Trust Barometer, which has published a report on worldwide trust every year since 2000. Guess what the report says this year?

We don’t trust very much right now.

Trust is down in every sector. Both media and government are perceived as unethical and incompetent. NGOs are still perceived as ethical—but not as competent. The only sector perceived as ethical and competent both is business. Talk about society flipping upside down.

The Edelman Trust Barometer doesn’t give advice, just survey data. Nevertheless, it’s pretty telling. We trust our government leaders less than we did a year ago. Same for religious leaders, journalists, people in our local communities, our employers, and even scientists.

What are we supposed to do about this? Also, given the very real environment of false information, deliberate deception, and violations of integrity, is lack of trust a problem or a sensible response to our circumstances?

Sara Niccoli, our speaker for the Quaker brown bag lunch this week, suggested a possible solution to a lack of trust: we can try to create a system we trust, a democracy that will serve us, upon which we can rely. But—and this is my interpretation, not Niccoli’s words—that seems to imply that one way out of the current trustless system is to ensure that we never find ourselves in positions where we are genuinely vulnerable. If I can build a system that shelters me from the impact of your actions, then what you do or say doesn’t matter. I’m safe anyway.

I don’t see how that works. As I talked about last week, the future is reliant upon the actions of the entire worldwide community. We are all in this together, like it or not. Systems designed to protect us from each other can only get in the way of holding each other tight. We’re going to have to address the situation of mutual trust.

But again—the week’s conversations and lectures at Chautauqua shied away from that. Instead, we talked about patterns in society: reparative journalism, cancel culture, societal fracturing through social media. Even the interfaith lectures didn’t really address mutual trust; they went, instead, with the theme of “the ethical foundations of a fully functional society.”

I kind of understand the hesitancy. Trust is a really hard topic. To rebuild trust after genuine harm—and we are absolutely experiencing genuine historical and ongoing harm—requires mutual commitment, empathy, mercy, repentance, forgiveness, and redemption. The very idea feels almost absurd. It’s certainly beyond our human capacity—which is why we need to be calling on God.

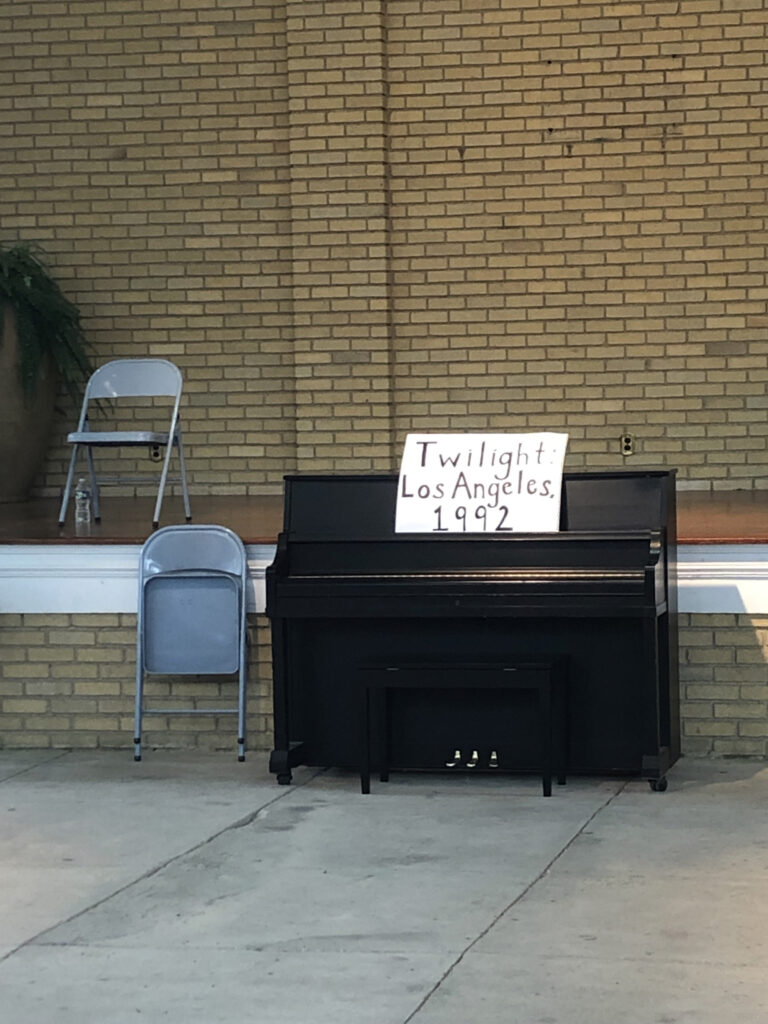

The best glimpse of a first step happened Friday afternoon. About a hundred people traversed monsoon-like rain to attend a free performance of Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, a documentary theatre piece about the aftermath of the 1992 verdict following the beating of Rodney King. This one-woman play is constructed entirely of monologues drawn from real people’s real words. Smith, the playwright, interviewed everyone from Maxine Waters to Rodney King’s aunt to jury members to gang leaders to a wealthy white real estate agent to a Korean grocer, and in the play, a single actor embodies each of these humans one by one.

After the performance was a brief Q&A, and one man asked, “How do you play all these roles? How do you step into the shoes of so many different kinds of people?”

Actor Regan Sims replied, “Well, Anna Deavere Smith is very wise in what she says about this. She says it has to be without judgment, just believing that these people are real human beings, that what they say and the feelings they’re expressing are genuine. Whatever someone says about their own experience, even if—even if—you just have to trust them.”